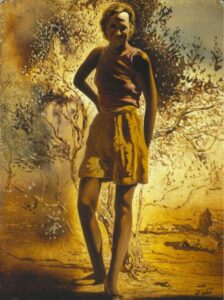

Dalí writes of imagining and dreaming of her long before their decisive meeting, in the summer of 1929. The impact she had on the artist was intense and passionate. The vision of her naked back with the sea beyond her was forever engraved in Dalí’s memory, and is in ours, through his work.

Gala is continually defined and redefined under the painter’s gaze. The first Galas to appear are sophisticated, sensual, provocative women as can be seen in Portrait de Gala (c. 1933) where the woman’s real fleshy corporeality is manifest. All of these Galas have a penetrating gaze, which Paul Éluard described as being capable of piercing walls.

In the context of Dalí’s turn towards a more mystical quality in his painting that Gala adopts a new archetype: that of the Virgin Mary. Dalí transformed Gala into a true divinity, embodying all the serenity of the Immaculate Conception itself. This was far more than an aesthetic gesture, implying as it does a profound symbolic charge: Gala, a divorced Russian woman, is sanctified and elevated to the sacred status of a Madonna.

The landscape of Portlligat, which for Dalí represented a personal paradise, is transformed here into a stage framed by curtains which suggest theatricality and illusion.

“Portlligat is the place of realizations. It is the perfect place for my work.

Everything conspires for it to be so: time passes more slowly and each

hour has its just dimension.”

Salvador Dalí

Francisco Valenzuela, “Granada es una ciudad geométrica”, Patria, Granada,

07/06/1957.

Dalí needed the spiritual strength of that special place.

Aware that he could not create it anywhere else, he painted it in Portlligat, in his studio, by the sea, which became the background of the work, the setting.

“I need the localism of Portlligat as Raphael needed that of Urbino, to reach the universal by the path of the particular.”

Salvador Dalí

José María Massip, «Dalí, hoy», Destino, Barcelona, 01/04/1950.

Several other objects levitate in space, alluding to the dematerialization of matter and reflecting the artist’s fascination with modern science.

Within this universe ordered according to its own logic, Dalí condenses his entire personal cosmogony into a single landscape. “Each object expressed by me in painting has today reached its maximum of significance.”

Salvador Dalí

The Madonna of Port-Lligat», Carstairs Gallery, New York, 1950-1951.

Bread, for example, is once again given a central importance in the composition, where it constitutes a spiritual and artistic core, symbol of the Eucharist. “In the centre of the painting, in the heart, in the opening that the child has in his chest, I shall paint a basket with a loaf of

white bread, which I want to be the vital and mystical

core of my weightless Madonna, sheltered under an

arch in the middle of my landscape.”

Salvador Dalí

Josep Maria Massip, «Dalí, hoy», Destino, Barcelona, 01/04/1950.

Crustaceans and molluscs, so recurrent in Dalí’s imagination, are among the other significant elements here. The sea urchin, with its perfect geometric structure, becomes a metaphor for the cosmos and divine perfection and, according to Dalí, is even a resource which the painter must always have close at hand when working.

The Madonna is decorated with an amalgam of Dalinian symbols and objects: a cloth, an olive branch, the jasmine flower, roses, a fish, an olive and a pottery bowl. Most of these elements appear in other works by the artist and some could be allusions to typical aspects of the Mediterranean world. They could even refer to Gala: Oliveta is one of the nicknames by which Dalí calls her.

Dalí always considered the Renaissance to be the era in which he would

ideally have liked to live; a period in which, according to the artist, the

splendour of the means of artistic expression was achieved. He would have

liked to live in a time when nothing needed to be saved,

but he, as his name suggests, was destined to “rescue

painting from the void of modern art.”

Salvador Dalí

The Secret Life of

Salvador Dalí, Dial

Press, New York,

1942.

According to Dalí:

“Modern artists will not touch religious subjects because

their technique cannot compare with the magnificent art

of the Renaissance.”

Salvador Dalí

Peter Hastings,

“Surrealist artist

designs strange

jewellery”, The

Australian Women’s

Weekly, Sydney,

10/02/1951

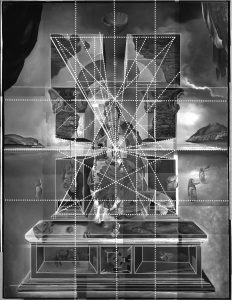

In Dalí’s The Madonna of Portlligat we find clear references to Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. In both the composition is frontal and the work is conceived as a true theatrical scene. The green curtains in the Raphael painting, and the green and red in Dalí’s, take us onto the stage and into the performance. In the centre, like a revelation, Mary appears with the baby Jesus.

The motif of

the egg suspended from the apse shell, which Dalí considered

to be “one of the greatest mysteries of the painting of the Renaissance”, is clearly an allusion to the Montefeltro altarpiece by “the divine Piero della

Francesca”.

Salvador Dalí

50 Secrets of Magic Craftmanship (1948).

«The Madonna of Port-Lligat», Carstairs Gallery, New York, 1950-1951.

It is not only the dimensions of The Madonna of Portlligat that recall the great altarpieces of Raphael and Piero della Francesca but also the colours chosen by Dalí, blue and gold, which are clear references to the Renaissance era.

Beyond the surrealist Dalí who captivated the world, from the 1940s on, he iniciated a spiritual research to find faith. “At this moment I do not yet have faith, and

I fear I shall die without heaven”. He

returns to

the great classical themes, now enriched with the scientific knowledge and the experiences of the Spanish mystics who fascinated him so much, bringing a turning point in his painting: the nuclear mystical era.

Salvador Dalí

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942)

The great weight of atomic physics and the disintegration of the atom, together with the representation of lightness and buoyancy, can be appreciated in this painting.

The relationship between weight and lightness is fundamental to understanding the construction of this image: “Everything that weighs does not weigh,

and what is more weightless is held down by a string.”

Salvador Dalí

Rafael Santos Torroella, «Con Salvador Dalí, en Portlligat», Correo Literario, Madrid, 01/09/1951.

The atomic explosions of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 shook the foundations of humanity. This

tragic historical event, revealing for Dalí, captivated him intensely, and

the atom became the main focus of his artistic and philosophical interest.

As the artist himself confessed to Parinaud: “Thenceforth the atom was

my favorite food for thought.”

Salvador Dalí

André Parinaud, Confessions

inconfessables (1973).

And so it was that Dalí embarked on an intense period of study, immersing himself in readings on nuclear physics to understand those phenomena that questioned traditional conceptions of matter and reality. His studies on the structure of atoms directly influenced his works from the late 1940s, when objects that float in space begin to appear, as in Atomic Leda (1947-1949)

This visual representation of the discontinuity and decomposition of matter is progressively accompanied by religious themes such as the crucifixion, exemplified by The Crhist(1951), or the Virgin and Child, with the two versions of The Madonna of Portlligat (1949 and c. 1950).

Despite appearing to have a single vanishing point, the work actually combines several points, especially around the pedestal. In the latter, we find several objects: a sphere, a rhinoceros, a melted bust; all of these elements share the same alternative vanishing point. This multiplicity of points creates an artificial, impossible perspective, generating an oneiric, unreal effect.

Dalí uses what is called accelerated perspective, a technique based on modifying the scale of the images to create a dramatic illusion. In The Madonna of Portlligat, the artist takes this resource further: he combines several vanishing points and accentuates the exaggerated perspective, creating a visual illusion that manipulates reality.